When war broke out in Europe in 1914, there were immediately dissenters who would not cooperate with the military. In Great Britain and its empire, men were conscripted by the tens of thousands; out of these approximately 16,000 became conscientious objectors to war. They were often greatly mistreated (see The Peace Pledge Union for more information). Their stories were told on this side of the Atlantic and provided inspiration to American conscientious objectors (C.O.s) when the U.S. entered the war in 1917. In many other European countries conscientious objectors were imprisoned or, in some cases, even executed.

In the U.S. Church denominations with long histories of peace witness (Mennonite, Amish, Hutterite, Dunkard / Church of the Brethren, Religious Society of Friends / Quaker) produced many American objectors; these men were joined by members of pacifist sects from the newer waves of immigrants, such as the Molokans and the Doukhobors, who had come from Russia after 1903 to escape service in the Czar's army. There were also many Jehovah's Witnesses, who claimed religious exemption from military service (all JW adult male were considered "ministers"). In addition there were political objectors such as the Socialists, humanitarians, and members of the I.W.W. (International Workers of the World), and those who simply did not believe in war or in that particular war.

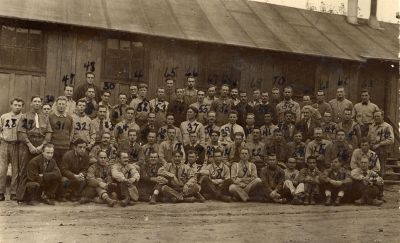

The C.O.s in World War I were sent to military camps where they had to convince officers and other officials that they were sincere in their conscientious objection to war, which, at times, resulted in abuse from the enlisted men. One unofficial source states that 3,989 men declared themselves to be conscientious objectors when they had reached the military camps: of these, 1,300 chose noncombatant service; 1,200 were given farm furloughs; 99 went to Europe to serve with the Friends Reconstruction Unit; 450 were court-martialed and sent to prison; and 940 remained in the military camps until the Armistice was fully enacted in 1918. Recent scholarship, though, has revealed that the number was closer to 5,500 (at least), not counting the men who immediately signed up to go into the noncombatant branches of the military rather than declaring themselves to be conscientious objectors.

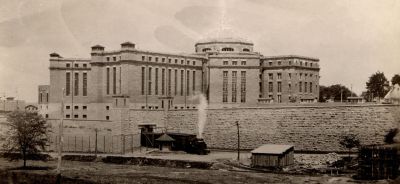

The absolutist C.O.s who refused to drill or carry out any noncombatant service were sentenced to many years of hard labor in federal prison at Alcatraz Island or Ft. Leavenworth U.S. Disciplinary Barracks, often suffering persecution, manacling, and solitary confinement. Most C.O.s who had been imprisoned were released by May of 1919, though some of those thought to be the most recalcitrant were kept until 1920. At least 27 C.O.s died, mostly while in prison.

The stories of C.O.s during the Great War were kept alive over the next decades, especially by members of the Mennonite Church and other peace churches. This engendered a desire to find a way to keep their young men from the same ill treatment when drafted for World War II. The lobbying done with the War Department led to the creation of Civilian Public Service and to I-W Service, alternatives for conscientious objectors to military service that existed in various forms through the end of the Vietnam War.

The Swarthmore College Peace Collection has dozens of primary source collections of documents, photographs, posters, and other materials on conscientious objection during World War I, and from around the world. These are organized into collections of the records of grassroots peace organizations or the papers of peace activists. The collections listed below have online finding aids (lists of documents folder by folder), or image collections available on line. The Peace Collection has many additional collections which are not yet online, but are available for research.

The Peace Collection is open to the general public throughout the year. See the full website at: http://www.swarthmore.edu/Library/peace

By Anne M. Yoder, Archivist, Swarthmore College Peace Collection [AMY]

![“I Didn’t Raise My Boy To Be a Soldier”, Sheet Music [cover], by Alfred Bryan and Al Piantadosi, 1915](/application/files/thumbnails/lite_gallery/2616/2385/4655/0235.jpg)

The Swarthmore College Peace Collection has dozens of primary source collections of documents, photographs, posters, and other materials on conscientious objection during World War I, and from around the world. These are organized into collections of the records of grassroots peace organizations or the papers of peace activists. The collections listed below have online finding aids (lists of documents folder by folder), or image collections available on line. The Peace Collection has many additional collections which are not yet online, but are available for research.

“Conscientious Objection in America: Primary Sources for Research”

William Kantor Collected Papers

New York Bureau of Legal Advice Collected Records

No-Conscription Fellowship (Great Britain) Collected Records

Subject File on Conscientious Objection/Objectors

Database of Names and Other Information on WWI C.O.s

“Military Classifications for Draftees”

Opposition to the War in the United States

Peace Congresses Leading Up to World War I

Quaker Civilian War-Relief in the Great War and its Aftermath, 1914-1922

Women Peace Activists During World War I